by Allie Lowy

Three months after the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released its most alarming report to date, rendering human-caused climate change a “code red for humanity,” and following an apocalyptic summer with unprecedented wildfires, heat records, and flooding around the world, world leaders gathered in Glasgow for the 26th Conference of the Parties — COP 26 — to effectively maintain business as usual. In a summit marked by compromise, greenwashing, and lukewarm promises, the free world revealed just how beholden to fossil fuel interests it remains, despite the increasingly uncertain future of humanity’s future on Earth.

Brief primer on climate pledges

Climate Conferences are generally defined by the final agreements reached in the summit’s final days. In Paris in 2015, 197 countries agreed to curtail emissions to limit human-induced warming by 2100 to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. The 1.5 degree target isn’t arbitrary: it is the point beyond which, scientists agree, a number of irreversible climate tipping points and runaway feedback loops could be triggered, and the risk of extreme drought, wildfires, floods and food shortages increases dramatically. As of 2021, the Earth has already warmed 1.2 degrees; keeping warming below 1.5 degrees is increasingly unlikely. Worse yet, with the world’s current emissions trajectory, we’re slated to reach at 2 degrees warming — another key “point of no return” — by 2043, and between 3.5 and 8.6 degrees warming by 2100, at which point human life on Earth would look very different.

Finally, climate science tells us that the world could achieve 1.5 degrees Celsius if it reached net zero carbon (not emitting any more carbon than is absorbed) by 2050.

Now that you’re caught up on what’s at stake, let’s delve into what came out of the conference.

The Final Agreement (“the Glasgow Climate Pact”):

- (1) It “urges parties to revisit and strengthen the 2030 targets in their nationally determined contributions, as necessary to align with the Paris Agreement temperature goal by the end of 2022,” when countries will meet again. Experts state that this clause “keeps open the door to the 1.5 degree goal.” My take: This is a cop-out that gives world leaders a false sense of complacency and pushes solving the climate crisis back another year. This doesn’t accomplish anything new: it is a gentle reminder of the binding agreement the world agreed to 6 years ago. Most of the globe remains far from reaching this goal.

- (2) It asks countries to “make efforts to reduce usage of coal as a source of fuel, and abolish ‘inefficient’ subsidies on fossil fuels.” My take: This is watered down, loophole-laden language. The research is clear: the world needs to phase out coal by 2040 — and developed nations by 2030 — to have any hope at 1.5 degrees. The Glasgow Climate Pact mentions no such phase-out. Asking countries to “reduce usage of coal” is weak language; it doesn’t state by how much, by what year, and isn’t binding. At the very least, they could have abolished fossil fuel subsidies altogether, but that “inefficient” qualifier leaves open the possibility of subsidies for some remaining coal generation.

- (3) It “requests the secretariat to produce an updated version of the synthesis report on nationally determined contributions under the Paris Agreement annually.” My take: The latest synthesis report was alarming — it indicated that, if countries followed their current nationally determined contributions, greenhouse gas emissions would be 14 percent above 2010 levels by 2030. These synthesis reports used to be every five years, but now they’ll be annual, which is promising. To be sure, this is progress — monitoring and modeling is good — and could be meaningful if coupled with mandates and accountability measures that actually require emission reductions.

- (5) It “creates a two-year work programme to define a global goal on adaptation.” My take: a first-of-its-kind nod to adaptation. The world has had a global goal on mitigation (Paris Agreement), but no such goal for climate adaptation. Adaptation is arguably the most important issue for developing countries — who did the least to cause climate change, are the most burdened by it, and have the least capacity to adapt to it and build resilience. Devoting a working group to addressing global environmental injustice is a good first step.

- (6) It “asks the developed countries to at least double the money being provided for adaptation by 2025 from the 2019 levels ($15 billion).” My take: This is something, if they can make good on this promise (unlike the $100 billion promise developed countries twelve years ago that they are far from fulfilling). Still, it’s not nearly enough to meet the need; many developing countries left the summit feeling unsatisfied by this.

Other takeaways from the negotiations:

(1) Many countries reached a landmark bill on deforestation.

141 countries, including Brazil — home to the Amazon — representing more than 85% of the world’s forests, agreed to end deforestation by 2030. They allotted $19 billion in public and private funds to this — including to help poor countries restore degraded land, tackle wildfires, and support indigenous communities.

My take: This could be the most significant commitment made at COP 26, if taken seriously. Curbing deforestation is crucial because forests absorb about a quarter of the carbon the world emits annually. I would like to see individual countries pass concrete policies in line with this goal, though, because in 2014, a similar “landmark” global agreement on forests failed to slow deforestation in any way.

(2) Some countries and financial institutions committed to stop financing overseas fossil fuel projects by 2022.

33 nations and 5 financial institutions — including the U.S., U.K, Canada, Italy, Germany, Denmark, and the European Investment Bank — signed on. If implemented correctly, this agreement would mean at least $18 billion of international public financing switching from supporting fossil fuels to clean energy. China, Japan, and South Korea — which account for nearly half of international funding for fossil fuel projects — were notably absent from the agreement.

My take: Also notably absent were the top four biggest funders of international fossil fuel projects: JP Morgan Chase, Citi, Bank of America, and Wells Fargo. American banks will be key players in the just transition to renewable energy. There are also a couple caveats: this doesn’t affect existing funding for fossil fuel projects — it only prevents new funding. The wording also leaves room for loopholes: “We will end new direct public support for the international unabated fossil fuel energy sector by the end of 2022, except in limited and clearly defined circumstances that are consistent with a 1.5°C warming limit and the goals of the Paris Agreement.” That “unabated” qualifier — and the clause about circumstances — were thrown in last-minute to offer some wiggle room to still fund fossil fuel projects. For instance, unabated refers to projects that doesn’t use carbon capture technologies, so this agreement allows funding for those that do. Carbon capture tech is largely undeveloped, and cannot currently be relied upon to offset emissions. Still, this is a landmark agreement. Plus, even though China, Japan and South Korea didn’t sign on to this agreement, they’ve committed to ending overseas coal financing, which means all significant public international financing for coal has effectively ended. This is pretty huge. Now, to tackle oil and gas…

(3) Forty countries agreed to phase out coal by 2030 for bigger economies and 2040 for smaller economies.

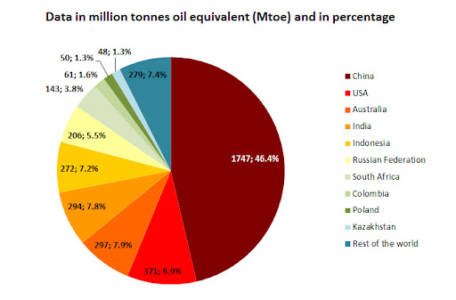

Some major coal producers — including Indonesia, Poland, South Korea, Germany, Ukraine, Canada, Kazakhstan, and Vietnam — committed to phase out their use of coal for electricity generation, with the bigger economies doing so in the 2030s, and smaller economies doing so in the 2040s. However, the world’s biggest coal users, including China, India, the U.S, Colombia, Australia, Russia, and South Africa, were missing from the deal.

My take: the 2030/2040 targets technically align with Paris, but we need to get the world’s biggest coal producers to commit to them.

(4) Despite some new climate pledges, climate pledges still fall short of meeting Paris benchmarks, and there’s a disparity between pledges and actual policies to reduce emissions.

More than 130 countries have agreed to reach net zero by 2050 thus far: new additions to the list include Brazil and Israel. China, the world’s largest carbon emitter, has committed to net zero by 2060, as has Saudi Arabia, the world’s second largest oil producer, and Russia, the world’s second largest gas producer, who has yet to legally ratify this commitment. India, the world’s third largest carbon emitter, committed to net zero by 2070.

My take: Still, even with the new climate pledges made in Glasgow, assuming that all countries perfectly meet their climate commitments, in our current best case scenario: we’re still forecasted to see at least 2.1 degrees warming, overshooting Paris by more than 0.6 degrees and pushing us past that dangerous, 2 degree point after which many life-sustainability natural processes go South. Plus, we shouldn’t assume that countries’ climate targets will be met, as there’s currently a large gap between climate pledges and national policies in place to ensure we achieve these targets. A recent study suggests that countries are slated to produce more than double the amount of fossil fuels in 2030 than what would be in line with Paris. This is probably an understatement, as there’s evidence to suggest that most of the world is underreporting its emissions.

Tuvalu’s prime minister stands in a lectern knee-deep in seawater to illustrate the effects of climate change. Credit: list23.com.

(5) Tensions between developing and developed nations escalated, and developing nations left feeling unsatisfied with minimal funding for climate adaptation.

Tensions between developing and developed nations ran high in Glasgow: as poor nations (rightfully) called the developed world out for failing to provide funding for them to cope with climate change: a problem that poorer nations did little to create, disportionately bear the impacts of, and have the least resources to cope with. The foreign minister of Tuvalu, a low-lying Pacific island nation, even gave a speech at a lectern knee-deep in seawater to illustrate the country’s vulnerability to sea level rise.

Twelve years ago, developing nations agreed to provide $100 billion in annual funding to vulnerable nations by 2020, which would include mitigation efforts, and, importantly, adaptation projects to help protect communities against climate impacts. However, this $100 billion goal is still elusive, and likely won’t be met until 2023 or later.

My take: It’s also worth mentioning that the majority of the funding is for mitigation (emissions reductions), rather than adaptation projects, which make communities resilient to the impacts of climate change. When most of these vulnerable nations emit very little per capita to begin with, mitigation funding is kind of a slap in the face, and not where funds should be directed when these countries are on the frontlines of the climate crisis.

The $100 billion amount is also far below the need. A U.N. report estimates that funding for climate adaptation should be five to 10 times greater than what’s currently being spent.

(6) Fossil fuel representation was immense.

503 fossil fuel delegates attended COP 26: more delegates from fossil fuel interests than any other country, and more delegates than all of the small developing island nations combined. Many point to this as a reason for much of the watered-down, compromise language that revealed the world’s still-strong ties to fossil fuel interests.

My take: the absurdity of this is self-explanatory. It’s like if wolves were the largest delegation to a conference on the survival of sheep.

(7) COP 26 was the most exclusive Conference of the Parties to date, which called its legitimacy into question.

A number of organizations said that restrictions on access to negotiations were unprecedented and unjust. Observers representing hundreds of environmental, academic, climate justice, indigenous and women’s rights organizations warned that excluding them from negotiating areas could have dire consequences for millions of people. Asad Rehman, a spokesperson for the COP26 coalition, estimated that only one-third of the usual number of participants representing the Global South had been able to attend the conference. To make matters worse, COP 26 was sponsored by large corporations that are some of the world’s worst polluters. Many activists criticized the summit as a dramatic display of corporate greenwashing with unbridled corporate influence.

To close, I leave you with a quote from Swedish teen activist Greta Thunberg:

“It should be obvious that we cannot solve a crisis with the same methods that got us into it in the first place…We need immediate drastic annual emission cuts unlike anything the world has ever seen. The people in power can continue to live in their bubble filled with their fantasies, like eternal growth on a finite planet and technological solutions that will suddenly appear seemingly out of nowhere and will erase all of these crises just like that. All this while the world is literally burning, on fire, and while the people living on the front lines are still bearing the brunt of the climate crisis.”