We are creating a model for collaboration among community members to design and create food-producing green spaces in urban neighborhoods. Looking to get involved in other agriculture-related climate change solutions? Join the 350 Colorado Regenerative Ag Committee!

Description and Benefits:

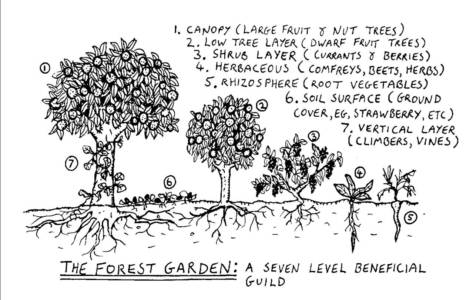

A food forest is a gardening technique or land management system, which mimics a woodland ecosystem by substituting edible trees, shrubs, perennials, and annuals.

Fruit and nut trees make up the upper level, while berry shrubs, edible perennials, and annuals make up the lower levels.

Food Forrest Characteristics:

- Low maintenance

- Self-sustaining

- Supports ecosystem

- Fruits, berries, nuts, herbs, fibers, flowers, dyes.

This project seeks to contribute to the movement of sustainable local food production through community-driven urban agriculture, or “food forests”. Similar efforts have been shown to improve “fresh vegetable production, physical activity, green space, job creation, storm-water retention, greenhouse gas mitigation, neighborhood beautification, ‘eyes on the street’, and community-building.” Community shared agriculture efforts “have strengthened communities, fostering multi-ethnic and multi-generational exchanges of food … knowledge.”

In addition, they can contribute to democratization and citizen involvement in our communities. They “can foster civic engagement by creating inclusive spaces for public participation and for social learning about food production and consumption…[and] ‘cultivate the political and social skills necessary for effective citizenship’.” The more we can solidify these patterns of social interaction, the more we can make our voices heard as citizens working to solve our most difficult challenges, like climate change.

Community-led urban agriculture also has implications for broader systems and structures. “Emphasis on food and agroecological citizenship privileges public over private gain, framing healthy food as a public good and access to it an unalienable right that cannot be left to the logic of the market… Urban agriculture and other [alternative food networks] can ultimately serve as a counter-hegemonic tool to reclaim ‘the commons’ from the enclosure of capitalist commodification by ‘ensur[ing] that access to basic life-goods like food can be met through non-commodity channels, particularly when sufficient purchasing power is lacking’.” It does this, by working to “re-localize or reconnect production-consumption linkages separated by the industrial agri-food system.”

With these in mind, community collaboration on urban agriculture such as we propose can go a long way toward creating a sustainable and climate-aware culture.

Neighborhood food forests in urban parks have proven viable in cities all over the world.

Neighborhood food forests in urban parks have proven viable in cities all over the world.

Resilience.Org lists 20 successful projects from around the globe in which permaculture designers, landscape architects, and community members have come together to share knowledge and skills, and put them into action in their neighborhood green spaces.

Ben Nobleman Park in Toronto, ON has a community orchard in which volunteers maintain 14 fruit trees, much of the harvested fruit goes to the local food bank, and the space is used to host

“blossom and fruit festivals, pruning workshops, orchard picnics, children’s educational workshops, and other community events”

In London, UK, The Urban Orchard Project has created dozens of urban food forests at schools from elementary to university, affordable housing sites, apartment complexes, a hospital, and city open spaces. The Resilience.Org article linked above includes successes in a number of US cities as well, including Asheville, NC; Austin, TX; Bloomington, IN; Boston, MA; Glendale, OH; Los Angeles, CA; Madison, WI; Philadelphia, PA; San Fransisco, CA; Seattle, WA; Tacoma, WA; and Youngstown, OH.

Check out this video from the Central Rocky Mt. Permaculture Institute on Basalt Mountain.

With all of their potential benefits, we want to see projects like these become a reality here in Boulder and to make them feasibly replicable in communities around the world. Rather than handing all of the design and construction processes over to hired professionals, communities need the opportunity to share that responsibility in order to reap all of the benefits.

With all of their potential benefits, we want to see projects like these become a reality here in Boulder and to make them feasibly replicable in communities around the world. Rather than handing all of the design and construction processes over to hired professionals, communities need the opportunity to share that responsibility in order to reap all of the benefits.

With all of this in mind, we are creating a model that will provide such an opportunity, bringing residents to the table with multiple organizations, experts, and professionals to design their own neighborhood green spaces. Edible landscapes have begun to appear in the most progressive cities in the US and elsewhere, and we want to see that accelerate; it is time that Boulder becomes an example of how our cities can foster civic participation and collaboration through food-producing green spaces. Not only is this a small type of climate change solution, it’s also a smart way to support our local community.

Planned Action Steps:

- Organize and host gatherings, discussions, and workshops with landscape designers, city parks officials, and local residents to plan renovations to their parks. We will provide childcare and food for these.

- Organize and host workdays to break ground in local parks with neighborhood residents and volu

nteers. This will include obtaining soil amendments, trees, seeds, support structures, etc., as well as advertising the workdays and recruiting outside volunteers.

nteers. This will include obtaining soil amendments, trees, seeds, support structures, etc., as well as advertising the workdays and recruiting outside volunteers. - Continue bringing in different organizations that might have an interest in collaborating on these projects. There are organizational roles for everything from supplying resources, to contributing labor, to providing future educational programs to be offered in these spaces.

Collaborators Currently Include:

350CO, University of Colorado INVST Community Leadership Program students, multiple University of Colorado Faculty, Permaculture Designers from Rockies Edge Permaculture Institute and other Boulder residents. The project idea came out of the Edible Landscapes Coalition, a committee of The Shed (Boulder County Foodshed), which is a coalition of City, County, BVSD schools, CU, and nonprofits and businesses promoting local food.

Key Benefits:

The project will bring community members together to participate in a shared project, empowering residents to create their own green neighborhood gathering spaces. This will, in turn, provide space for further community engagement and neighborhood relation-building. Unlike the community gardens we have come to know, this project enables communal gardening. Whereas the former consists of individuals tending their individual plots, the latter brings neighbors together to share the space in a way that builds real relationships.

Permaculture and place-making experts will assist in the design process, sharing their knowledge with community members about sustainable local and native food production. The space can provide some of that sustainable local and native food, which may be harvested by visitors, educating them about and connecting them to their local natural environment in the process. The ecological understanding developed through this interaction and knowledge sharing provides an important framework for viewing a world confronted by global ecological and human challenges like climate change.

Projects like this also make food production visible within our community and puts it into a truly local and immediate context, instead of relegating it to distant locales, large agribusinesses, and hidden externalities. Not only is this a smart climate change solution, but it’s also smart for our communities.

Valmont Park Food Forest – Check out this presentation about our proposal. Interested in helping bring a food forest to fruition at Valmont Park? Click here to join in and pledge your support. Thank you!

References:

Ben Nobleman Park Community Orchard. About Us. Retrieved from http://communityorchard.ca/about-us/

Ignaczak, Nina M. (2014). 20 Urban Food Forests from Around the World. Resilience. Retrieved from http://www.resilience.org/stories/2014-08-01/20-urban-food-forests-from-around-the-world

McClintock, N. (2014). Radical, reformist, and garden-variety neoliberal: Coming to terms with urban agriculture’s contradictions. Local Environment, 19(2), pp. 152-3.

OrchardPeople. (2016). Ben Nobleman Park Community Orchard. Basel Switzerland Learns About Ben Nobleman Orchard. Retrieved from http://communityorchard.ca/2016/01/17/basel-switzerland-learns-about-ben-nobleman-orchard/#more-1984

The Urban Orchard Project. Visit Our Sites. Retrieved from http://www.theurbanorchardproject.org/about-us/visit-our-sites